By Ed Staskus

Vilnius is the capital of Lithuania, although it wasn’t always the capital. As recently as the decades between the last century’s two world wars, the second-largest city Kaunas was the capital. Vilnius was controlled by Poland. After the Second World War it became the capital again, although Lithuania wasn’t exactly a country for the next 45 years. It was an SSR, like the rest of Eastern Europe, locked up tight behind the Iron Curtain. The Russians were masters of the land. Vilnius might as well have been Cell Block #1.

“The first time I went to Vilnius was in 1992,” Kristina Dambrauskas said. “I had never been there before. It was dismal.” It was two years after Lithuania declared its independence. They had repudiated the Brezhnev Doctrine in 1990 and said, “Russians go home!” They were the first of the Soviet SSR’s to do so. The Russians demanded they renounce their home rule claims. The Lithuanians said, “Go to hell!” A year later the Russians sent in tanks. They might as well have not wasted their time and firepower. By the end of 1991 the Soviet Union ceased to exist and the Iron Curtain went the way of the town dump.

Kristina lives in South Bend, Indiana with her dog Toto. She is a foreign language teacher at the nearby Mishawaka High School, specializing in Spanish and German. She often travels to Italy, Germany, and Switzerland. She spent two weeks in Cuba in 2016. Her mother and father were born and bred in Lithuania. They landed in the United States after World War Two made them refugees.

“I was living and doing a work study in Germany in the early 90s when I got a chance to go to Lithuania,” Kristina said. She flew from Frankfurt to Riga, Latvia. There were no direct connections. She was met by a cousin who lived in Vilnius. They drove back there. It was slow and slower going on the beat-up roads. “The city was dreary, full of decrepit Soviet stuff.” Everything was gray from one end of town to the other. “The trolleys were old, crawling along. There were potholes everywhere. Everything was run-down and rickety. The Russians were all about patchwork whenever anything broke.”

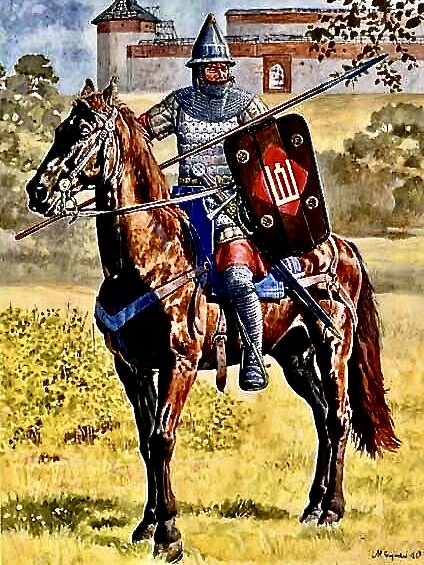

There were settlements in the vicinity of Vilnius from the Middle Stone Age onward. It became the capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1323. King Gediminas built a castle on top of a hill. Germany’s Teutonic Knights were upset about it and attacked the castle several times, failing to capture it. They burned the city down in 1365, 1377, and 1383. They wanted their revenge, no matter what shape it took. Late in the century England’s Henry IV threw his support and army of longbow archers behind the Teutonic Knights, to no avail.

When the Crimean Tatars started attacking Vilnius in the early 16th century the powers-that-be threw up defensive walls, including nine sturdy gates and three fortified towers. The Tatars didn’t accomplish much. They finally went back to Ukraine where they could drink their coffee in special cups called fildjan and read the Koran in peace.

After the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was created by the Treaty of Lublin in 1567, the city grew and flourished. Vilnius University was established in 1579. Craftsmen and tradesmen poured into the city. Jewish, Orthodox Slav, and German communities established themselves within the walls. Vilnius became the social, political, and economic hub of the region.

“Almost everybody seemed to be wearing hand-me-downs,” Kristina said. “There wasn’t enough food. They had to make do. There was a lot of begging, borrowing, and stealing. The stores were like flea markets. Everybody accepted it because they had no choice.” Most of the cars were Tatra’s, Dacia’s, and SMZ’s. They were among the worst built and ugliest cars in the world. The SMZ looked like a dumpster and had the aerodynamics of a cinder block. “Those cars went about as fast as lawnmowers,” Kristina said. No sooner did Lithuania gain its freedom than Lithuanians began racing to Germany and snapping up used BMW’s and Mercedes.

“My mother’s cousin Juozukas drove me to the Hill of Crosses,” Kristina said. His car was a Lada, an East German model. In its time it sold at the budget end of the market, in a market where the best cars were mediocre. “He was still married to Crazy Danute, so only the two of us went.” The Hill of Crosses is a stark memorial at the best of times. It was wintertime. It was even more stark under heavy clouds and near-zero temperatures. “It was a hill outside Siauliai with thousands of crosses. There was nothing else to see.” It got rough-hewn when the wind picked up.

Two weeks later Kristina went back to Germany. “Even though it was drab in Lithuania, I had a ball meeting my relatives.” The next time she went was in 1999. She was living in Cologne and working for an agency that catered to international students. She took a bus directly to Vilnius. The roads were more ship shape. “Everybody was friendlier than seven years before. The city was brighter. There were renovations going on everywhere. I spent a lot of time in Gizai, from where my mother came. My relatives drove me all over the place. They celebrated New Year’s while I was there. Everybody got as drunk as could be. They had a bonfire at midnight. It was a ton of fun.” As the clock ushered in the new millennium, she saw substantive changes all around her. There were fewer hand-me-downs. New shops and stores were opening all over. There were hardly any more crappy Soviet cars. There was plenty of food. The flood of natives emigrating somewhere else looking for a better life had slowed to a leak.

Vilnius was swept by flame in 1610. Everything was by-and-large built of wood. When the fires died down the city had to be rebuilt. In 1655 Russian siege engines appeared and Vilnius was eventually taken. Czar Alexis’s scorched earth policy was put into play. It was not a fun time. The city was pillaged, burned, and the population massacred. The death toll was more than 20,000. The Kremlin has never over-valued anybody else’s life. It took a long time for the city to get back on its feet.

When Kristina returned to Vilnius in 2012 she went with her sister Daiva and mother Ramute. They flew from Chicago by way of Copenhagen, getting to the homeland in 12 hours. She was astonished. “It was a world apart from what it had been,” she said. The country had joined both NATO and the European Union. The Parliament banned all displays of Soviet symbols. The Russians huffed and puffed. The decade since had been a robust one of economic growth. The average person finally had money in his wallet and her purse. The price of Big Macs went down until they were 40% less than the eurozone average. Big Mac lovers in Vilnius celebrated by dressing up like Ronald McDonald.

“There were as many new rental cars at the airport as there are back home,” Kristina said. “We rented a car, went all over, and stayed for two weeks. There was a lot of building going on.” When times are bad is as good a time to reinvent yourself as any. Lithuania may not have been reinventing the wheel, but it was busy realigning all four wheels at the same time.

“Oh, wow,” is what Kristina’s mother said after their first day there. She had fled Lithuania in 1944 as a child. Ramute, three siblings, her mother, and a cow tied to the back of their wagon made it to East Prussia, then to Bavaria, and finally to the United States a few years later, although the cow got left behind. Ramute’s father, a policeman, had been deported to Siberia in 1941, where he stayed and somehow survived for almost fifteen years. The last time Ramute had seen Lithuania it was a mess, the sky filled with bombs and smoke.

“The difference between winter and summer in Lithuania is the weather,” Kristina said. “Winter is cold and dark. We went in summer. It was warm. Everything was sunny and bright. I stayed with my dad’s cousin, Aldona, for a few days. She had a son who bought an old plantation the Russians left behind just outside of Vilnius. He revived it. There were almost no signs of Sovietness anymore in the country.”

Vilnius is old, very old, and new as can be. It has repeatedly brought itself back after acts of God and man-made disasters. There are 30 museums rich in its long past. The Old Town made the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1994. It features more than 1,500 medieval buildings. The Public Library is one of the oldest in Europe. Vilnius became a UNESCO Creative City of Literature in 2015. The city’s Tech Park is the newest and largest ICT hub in the Baltics.

It is a cosmopolitan city with plenty of diverse lifestyles. There is vibrant street art and sparkling nightlife far into the night. Vilnius was named a European Capital of Culture in 2009. It is known for its farm markets, hot air balloon rides, and music scene. In 1995 the first bronze statue in the world of the American musician Frank Zappa was installed near the center of the city. “My aesthetic is anything, anytime, anyplace, for no reason at all,” is what Frank Zappa always said. His statue reportedly winks at passers-by.

Vilnius is renowned as the City of Churches. It is a center of the Polish Baroque style of shrine. An early 17th century icon of the Virgin Mary, Mother of Mercy, is in a chapel at the Gate of Dawn. The city was once known as the Jerusalem of the North because of its large Jewish population and intense study of the Torah. There were more than 100 synagogues in 1900. That came to end in 1944 near the end of World War Two, after Germany’s Einsatzgruppen and Lithuanian collaborators slaughtered nearly every Jew in the country. Today less than half a percentage point of the population is Jewish.

The last time Kristina visited Vilnius was in 2018, again with her sister Daiva, and Daiva’s husband. “I stayed with one of our cousins. My sister stayed in a fancy schmancy hotel in the middle of town. It was beyond nice.” There were no more listening devices in the rooms. The phones didn’t make mysterious clicking sounds. The lights routinely turned on when switches were flicked on. Breakfast was continental and there were no more slices of tongue headcheese. Among other things, 2018 was the 100th anniversary of Lithuania’s earlier liberation from Moscow, which was gained in 1918. On top of that there was going on a Sokiu Svente, which is a dance festival, and a Dainu Svente, which is a song festival.

“We walked everywhere unless it was too far. That was when we called Uber. There were parties every night. I’m serious, every single night.”

Kristina went back to the Hill of Crosses before leaving for home. North American Lithuanians had raised money for a signature cross. She wanted to see it. “It was a big hoop-dee-da.” What she saw was a Hill of Crosses kept spic and span by independent people. There was a blessing and dedication of the new cross. There was a choir lifting their voices in sacred song. The hill was the same, but all around it there was newness. “There was a new visitor’s center, a new chapel, and a new parking lot. Busses were coming and going. There were even souvenir stands and a restaurant.”

However big the parties were in 2018, they were forgotten in 2023 when Vilnius passed out party hats to celebrate its 700th anniversary. A Festival of Lights kicked off the jubilee. The National Museum hosted an exhibition about the history of the city. The National Opera and Ballet Theatre reconstructed the first opera performed in Vilnius in the 17th century. The Biennial of Performance Art took performance art outdoors. There was rock ‘n roll, jazz, and classical music galore in the city’s parks. Hot air balloons hovered at the top of the world. Nobody did any mosh pit diving from the gondolas.

Every restaurant and watering hole in town stayed open around the clock to keep everybody’s strength up. Gastro expeditions popped up to find the best cold beetroot soup and craft beer. They weren’t hard to find. Vilnius is the capital of Europe for cold beetroot soup and craft beer. Some restaurants created historical cuisines, like Nelson’s zrazy and Jerusalem kugel. Diners were entertained with wild stories about the food.

Nobody who was there got much shuteye, but everybody who was there started making plans for the city’s 1000-year anniversary in 2323. They were sure it was going to be nothing short of a lalapalooza, something to remember forever. All they had to do was take their anti-aging vitamin pills and hold on until then.

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Atlantic Canada http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com.

A New Thriller by Ed Staskus

“Cross Walk”

“A once upon a crime whodunit.” Barron Cannon, Adventure Books

“Captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn. New York City. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye. The 1956 World Series. President Eisenhower at the opening game. A killer in the dugout.