By Ed Staskus

My name wasn’t always Johnny Cahill, just like Billy’s name wasn’t always Billy the Kid. Before I shot him my name was Johann Kallweit. I was from Konigsberg, a port city on the Baltic Sea in Prussian Lithuania. My older brother Pranciskus had left Konigsberg seven years earlier and gone to America. He worked in New York City for some months, after which he took the new transcontinental Pacific Railroad to Omaha, from where he happened upon a wagon train and ended up in the Arizona Territory. He took up blacksmithing. He shod horses for cowhands and rustlers. He lived outside Bonita, one hundred-some miles northeast of Tucson, sharing his adobe house with a Mexican girl near the Army post at Camp Grant.

The Mexican girl tended the beans and corn, the cooking and housework, and gathered buffalo chips for fuel. She washed his clothes at a creek bank, setting up rocks and building a fire, putting a zinc pail filled with water over the fire. She soaked the clothes in another tub and laid them down on a flat rock, soaping them and then pounding them. After rinsing them in the creek she cooked them in the zinc tub. After rinsing them again she hung them on sage bushes to dry.

My brother was known as Francis “Windy” Cahill in Arizona. After it was all over his undertaker told me he was called Windy because he talked more than most men. “He talked too damn much,” the undertaker said. “I always told him the more you say the more likely you are to say something foolish. I told him to talk low but he wouldn’t listen. He was always calling Billy a pimp. That’s what got him killed.”

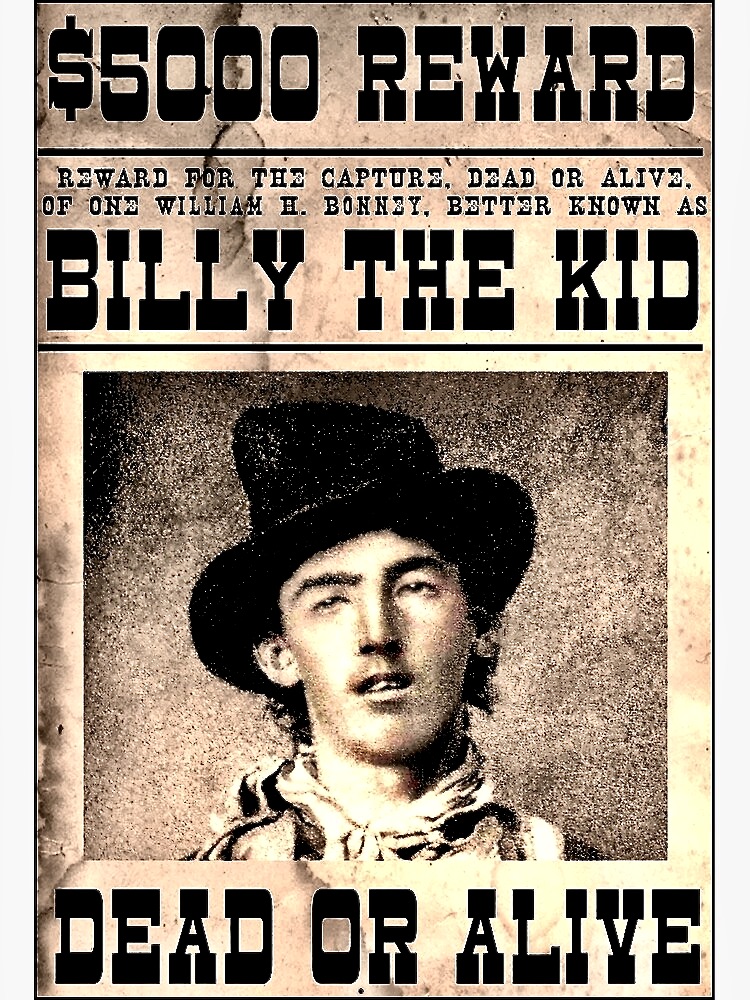

The outlaw Billy the Kid was born Henry McCarty. He was begotten in New York City in 1859, the same year as me in Konigsberg. He was the same age as me, almost twenty two years old, when he died on July 14, 1881, in Fort Sumner, New Mexico, on a cloudless night. Everybody thought the lawman Pat Garrett killed him. Everybody was wrong.

Henry McCarty was born on the east coast but when his father died the family moved to Indianapolis, where his mother met a new man. They uprooted to New Mexico to help with her cough. She died of tuberculosis a year later. In the end the southwestern air didn’t do her any good. The new man abandoned her two boys, leaving them orphans. Henry was 14 years old. He found work at a boarding house. When he was caught stealing food the man of the house beat him. When he robbed a Chinese laundry he was beaten and arrested. After he escaped by shimmying up a chimney, he stole clothes and handguns from his stepfather. They never saw each other again.

“People thought me bad before, but if ever I am truly free, I’ll let them know what bad means,” the boy becoming Billy the Kid said.

After I landed in New York City on my way to look for my brother I stayed for two weeks, learning more English. My bunkmate on the steamship voyage across the Atlantic Ocean had been an Englishman. He got me started. I spent my time in the city getting my bearings and seeing the sights. The sprawl was everywhere, dirty and crowded. There were more people than ever I imagined existed. There were tenements shoulder to shoulder. The rich lived in townhouses and mansions. I stayed on the Bowery where there were flophouses. It was where I met Nigger Dan. He was the first man from the Dark Continent I ever saw. He let me touch his oily coiled hair, but only once. When I asked him if he might be a cannibal he said, “No sir.” That settled my nerves about him.

We were in a Canal Street oyster bar eating shellfish and drinking lukewarm beer when he asked me what my plans were. I told him about my brother, about how I hadn’t heard from him but once in seven years. When I said I was going out west to try and find him, he said, “There ain’t nuthin’ here for me. Mind if I tag along?” He had no parents or relations. I told him I would be happy to have a companion.

We took the same Pacific Railroad to Omaha and the same trail to Arizona that my brother had taken. When we got to Bonita I found out while stopping in a saloon that he was dead. Billy the Kid, who by that time was going by the name of William Bonney, had killed him more than three years before.

“Your brother was always at Billy, elbowing him, calling him a worm and such,” the bartender told me. “Your brother was a big man with big hands. Billy wasn’t, more on the small side, looked even younger than he was. When Billy called your brother a son a of a bitch, Francis threw him down to the floor, pumping his fists into his face. Billy grabbed for his revolver, they struggled for it, and when Billy got a firm grip on it he shot your brother twice. He died the next day.”

A barfly listening in piped up, “He had no choice. He had to use his equalizer.”

Billy the Kid was arrested for the shooting by the Justice of the Peace. He was detained and held in the Camp Grant guardhouse but escaped before a U. S. Marshall could get there to take him to Tucson.

“I like to dance, but not up in the air,” Billy the Kid said, laughing and kicking his legs.

“Where did he go?” I asked. I was hell bent on running him to ground.

“New Mexico Territory,” the bartender said. “He got in with the Regulators and did some cold-blooded work in the Lincoln County War. He shot and killed Bill Brady the County Sheriff and one of his deputies. He got himself wanted dead or alive for killing that sheriff, which was when Pat Garrett ran him to earth down near Stinking Springs. He shot and killed Charlie Bowdre but took the Kid alive. He was tried and sentenced to hang back in May, but he busted loose, killing two more sheriff’s deputies on his way out the door. Pat Garrett is birddogging him right now.”

When the Lincoln County War was over, Lew Wallace, the governor of the New Mexico Territory, pardoned all the Regulators except for Billy the Kid. One day he got a letter. It was from Billy. It said, “I have no wish to fight any more. Indeed I have not raised an arm since your proclamation. As to my character, I refer to any of the citizens, for the majority of them are my friends and have been helping me all they could. I am called Kid Antrim but Antrim is my stepfather’s name. Waiting for an answer I remain your obedient servant.”

“Who’s this Pat Garrett?” I asked.

“The new sheriff there in Lincoln County. He took over from Brady. He’s from the south, I heard down Alabama way. He was a buffalo hunter in Texas for a while, then a cowboy driving cattle in New Mexico. He’s friends with Pete Maxwell up there, who’s got a big spread, just like Billy is friends with Pete, too. Hell, Billy was at Pat’s wedding two years ago.”

Pat Garrett and Juanita Martinez got married in the fall of 1879. After the ceremony, while they were dancing at the reception celebrating their wedding she collapsed, dying the next day. She was nineteen years old. Billy the Kid helped bury her. Three months later Pat Garrett married Apolinaria Gutierrez. She survived the ceremony and reception and was already nursing a newborn.

“Where can I find Billy the Kid,” I asked.

“It’s a ways to go,” the bartender said, “about twenty days of steady riding. It’s no secret what his whereabouts are, except nobody knows exactly where. How to go is go east to Las Cruces, where you can rest and feed your horses, and then north to Fort Sumner. The spring run-off was good this year, so you’ll find plenty of water. Be careful about Billy, he rides with four or five other outlaws and he’s got a hair trigger temper.”

Nigger Dan and I rode out to my brother’s adobe house to see where he had lived. There was nobody there. The Mexican girl was long gone. The beans and corn in her garden had gone bad, the leaf tissues shriveled and choked with weeds. My brother’s old dirty clothes were piled up in a corner. I was inside the house when a band of Indians rode up. They were Apache’s. One of them rode his horse into the house but when he found out he couldn’t sit up straight, bumping his head on the ceiling, he got off the horse and led it outside. I followed him.

All the Indians had Springfield rifles and well-filled cartridge belts. Two of them had pistols in holsters. The Indian who had gotten off his horse stepped up to me, put his hand under my chin, and pushed my head back. He reached for his Bowie knife. There was a clicking sound behind him. It was Nigger Dan at the far front corner of the house thumbing the hammers back on the Parker Brothers double-barreled shotgun in his hands.

The Indian in front of me put his knife away. He tapped his hands lightly on the top of his head before getting back on his horse. They rode away. We watched them until there was nothing to see. They were renegades. Most of the Apache’s had been forcibly moved onto the barren San Carlos reservation. We got on our horses and rode the other way.

Three weeks later we were in Fort Sumner. It was something like a town with mud-brick houses spread out helter-skelter. There was a dry goods store, a saloon, a livery stable and a smith, and a jailhouse, but no fort. It had been an Army post once, protecting settlers in the Pecos River valley and rounding up natives for resettlement. After Kit Carson corralled all the Indians he could find and pushed them onto the Bosque Redondo, the military base was abandoned. The cattle baron Pete Maxwell bought the post and rebuilt the officer’s quarters into a twenty room house.

“I tell you, stay your eye on the big house, amigo,” a vaquero told us, looking down at us from his flat-horned saddle. He was riding a black stock horse and wearing a low-crowned hat, a bolero jacket, and buckskin shoes with spurs. “That Billy, he visit there many times.”

We rode up to and around the big house. A short squat man came around a spool of new barbed wire and asked us what we wanted. He walked with a limp. He was chewing and spitting tobacco. “Get the hell away from here,” he said when I asked about Billy the Kid. “Don’t come back.”

We went back that night. The word at the nearby saloon was that Pat Garrett and two deputies were nearby. It could only mean Billy the Kid was nearby. I had gotten an old Whitworth sniper rifle in Omaha. It was the kind of rifle used by Confederate sharpshooters during the American Civil War. The graybeard selling it told me it was the very rifle that claimed the life of Major General John Sedgwick at Spotsylvania Courthouse on May 9, 1864. He was one of the highest-ranking Union officers killed during the war. Just before he was shot through the heart, sitting on his horse surveying the battle, after being warned that he was a target, Major General John Sedgwick’s last words were, “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance.”

The Whitworth was a British single-shot muzzleloader. Queen Victoria had fired the first shot from the first of the guns manufactured in 1860. She hit the bulls eye at four hundred yards. I poured powder into the muzzle of the rifle and pushed a ball down on top of the powder. I tapped it snug with a ramrod. I wouldn’t be able to get off a second shot so I didn’t fill my pocket with more balls and powder.

We waited for sundown before approaching Pete Maxwell’s big house. A dog barked and I tossed him a slice of prairie-chicken. “Billy be in a room around the back if he be anywhere,” Nigger Dan said. There was a grove of Ponderosa Pines around the back. I climbed halfway up one of the trees. From there I had a good view of all the bedroom windows. Nigger Dan handed the Whitworth up to me.

It was after midnight when I saw three men creeping through the Ponderosa Pines. One of them went to the back door and stepped into the gloom beside it. The other two men went around to the front of the house. Some minutes later somebody carrying a candle went into one of the bedrooms and woke up the sleeper. The man carrying the candle was Pat Garrett. The sleeping man was Pete Maxwell. I could see them talking. A slender man wearing a vest and a battered top hat walked up to the back door and went inside.

The man in the top hat soon appeared in the doorway of Pete Maxwell’s bedroom. There was a jack of diamonds tucked into his hatband. I didn’t like that. “Pete, who’s in there?” the man asked in Spanish. It was Billy the Kid. He was carrying a Colt Single Action .44 called the Thunderer in one hand and a slice of beef skewered on a knife in the other hand.

“Who is it?” Pat Garrett whispered to Pete Maxwell.

“That’s him,” Pete Maxwell said.

When Billy the Kid realized that somebody other than Pete Maxwell was in the shadows, he raised his handgun, aiming at Pat Garrett’s chest.

“Who’s that?” he demanded again as the lawman drew his revolver.

Even though I was an indifferent Lutheran, I quickly made the sign of the cross before squeezing the trigger. As I did I confessed to the shooting, so that I would become a witness to it rather than the man who carried out the deed. Pat Garrett fired a split second after I fired my Whitworth. My lead ball hit Billy the Kid in the chest. Pat Garrett’s bullet hit him in the same spot an instant later. The outlaw went down like a gut-shot grouse.

“He didn’t say anything,” Pat Garrett said. “A struggle or two, a little strangling sound as he gasped for breath, and the Kid was with his many victims. It was the first time, during all his life of peril, that he ever lost his presence of mind, or failed to shoot first.”

The lawman hadn’t listened closely enough. What Billy the Kid truly said while choking on a mouthful of blood was, “I never was no leader of a gang, I was for Billy all the time.” He died after speaking his piece. We helped bury him the next day in Fort Sumner’s old military cemetery, between his wrongdoing partners Tom O’Folliard and Charlie Bowdre. One tombstone was erected over the three graves with the epitaph “Pals” carved into it. I whispered “Geh zum teufel” while tossing a handful of dirt into the open pit.

It sometimes happens that even in Hell the damned aren’t always happy, just like the saved aren’t always happy in Heaven. I was sure Billy the Kid was damned. I wasn’t sure he was happy with his fate when it came to eternity, but I didn’t care overmuch about it. I had done what I had to do and revenged my brother by killing the man who took his life.

Nigger Dan and I set our sights on California. We heard it was a paradise with fertile land and ready access to water. The land was still cheap enough, even though many new settlers were pouring in. I took a stab at a map, spearing the County of Orange with my finger.

“We could try a citrus farm there.”

“That sounds fine, mighty fine,” Nigger Dan said as we rode our horses under a windswept sky on a sunny day down to the coastal plain of the Los Angeles Basin. He sang a song while we rode. It was from the American enslavement days. “Go down in the lonesome valley, my Lord, go down in the lonesome valley and meet my Jesus there. My brother, want to get religion? Go down in the lonesome valley.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street at http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Cross Walk” by Ed Staskus

“A Cold War thriller that captures the vibe of mid-century NYC.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction

Available on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CRPSFPKP

Late summer and early autumn, New York City, 1956. Stickball in the streets and the Mob on the make. President Eisenhower on his way to Ebbets Field for the opening game of the World Series. A killer waits in the wings. A Hell’s Kitchen private eye scares up the shadows.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication