By Ed Staskus

When my sister Rita told me our father was going to Lithuania to bring back the head of Vladimir Lenin, I was astonished. Lenin, who had died seventy some years earlier, was far more reviled than revered among Lithuanians. Most Lithuanians saw him as a callous ideologue whose policies led to another Russian occupation of their country in the 1940s. He was as bad as the Tsars. They blamed him for Josef Stalin, who ordered mass deportations whenever it suited him. They blamed him for the personal and political repressions that lasted nearly fifty years.

“You mean, like a memento?”

“No, more like a boulder-sized bust of Lenin’s head that weighs more than two thousand pounds.”

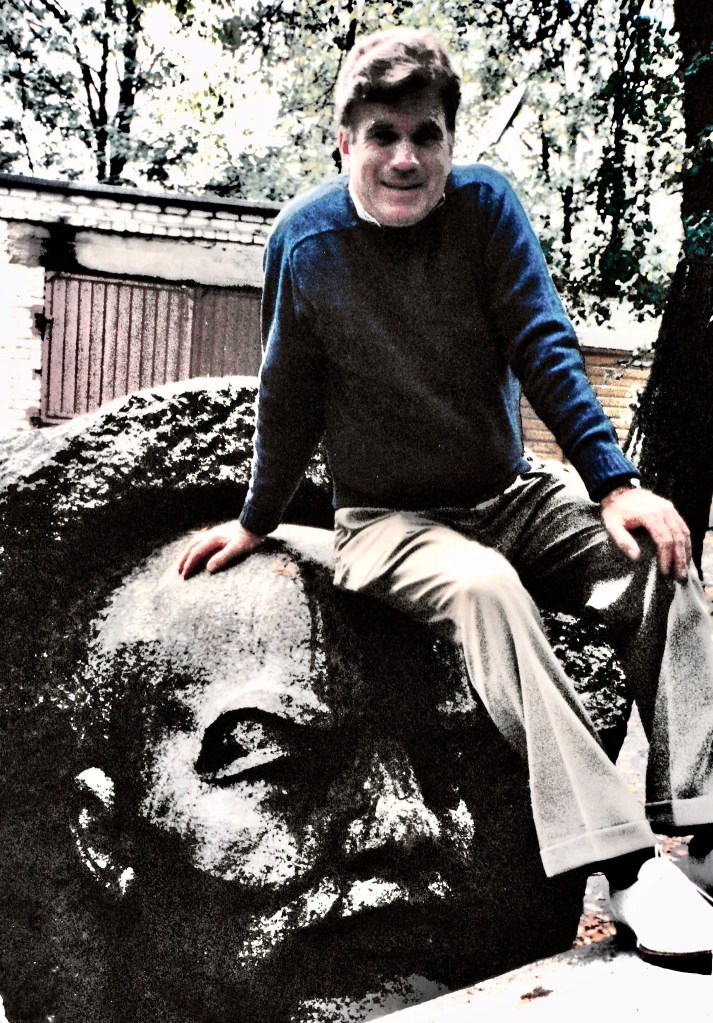

The boulder was the size of a Kamchatka bear. The face had been carved out of one side of the rock. Lenin looked untroubled. The boulder looked indifferent.

“What is he going to do with a head of Lenin once he gets it back to Cleveland?” My parents lived on the east side of Cleveland, near Lake Erie, a couple of blocks from the Lithuanian Catholic Church. They had a one-car garage that barely fit their car and a lawnmower. “Where are they going to put it?”

“It’s not for dad, it’s for Russell Bundy.”

“Who’s Russell Bundy?”

Russell Bundy was born during the Depression, the youngest of seven children. He would go on to have seven children of his own. At first, in the 1950s, he worked for a baking pan manufacturer but soon started selling pots and pans on his own out of the back of his car. Russell T. Bundy Associates was formed in 1964. They bought and sold refurbished bakery pans and equipment. They moved into what had been the Urbana Tool and Die Company building, about forty miles west of Columbus, Ohio, in 1972. They soon expanded their services and product lines, getting into pan-coating . Ten years later the American Pan division was formed to manufacture custom baking pans. In the 1990s what was now Bundy Baking Solutions added Dura Shield non-stick coatings to its family of brands.

As time went on Bundy Baking Solutions came to operate twenty six facilities in seven countries and employ more than one thousand people worldwide. The entrance to their headquarters was guarded by two grim looking stone lions. The beasts weren’t going to need a freshly baked hot dog bun if they decided to eat you.

“He’s helping this Russell Bundy person get his hands on a bust of Lenin in Lithuania and get it delivered to Ohio? How did that happen?”

Our father was born in Lithuania in the 1920s. His father was their district’s police chief. Our grandfather was swept up by the NKVD early during World War Two and transported to Siberia, where he was forced to work in a slave labor camp and died of starvation. Our grandmother was transported to Siberia in late 1944, for no apparent reason, and spent more than ten years trying to survive. When she was finally released she wasn’t allowed to return to Siauliai, where their home had been. She was forced to live in a one-room cinder block apartment in the middle of nowhere.

There was no love lost when it came to my father and the Russians. For all that, he was a retired certified public accountant and knew the value of a dollar. He was being well paid by Russell Bundy to go to the Baltics to help achieve his goals, although it was unclear what his goal was when it came to Lenin.

“Russell Bundy called me at the travel agency to get tickets to go to Lithuania.” My sister worked at Born to Travel in Beachwood, not far from where she lived in Cleveland Hts. “He asked me a hundred questions about towns and places, so I finally told him to call dad. He hired him go with him, to interpret, to navigate regulations, and find the right people.”

“Find the right people for what?”

“He was thinking of expanding into Eastern Europe.” It was the mid-1990s. He said Lithuania is ripe with business opportunities, the exchange rate is great, and there are lots of abandoned Soviet factories that could be converted to his use.”

“He’s probably right about that.”

They spent a week driving from the Zemieji Panieriai district in Vilnius to the Naujamiestis district in Kaunas to Klaipeda. The Baltic Sea port city of Klaipeda had become a major industrial hub during the Russian occupation of Lithuania from 1944 to the last troop withdrawals in 1993. In the end, Russell Bundy didn’t find what he was looking for. He did, however, find something else.

“He met an older Lithuanian man in Vilnius who had been a general in the Red Army,” Rita said. When the Russians left, he stayed where he was. He wasn’t a true-blue Communist, after all. A truckload of Red Army paraphernalia stayed with him. “He had a whole bunch of uniforms, medals, and military watches.” He had an assortment of gear and ephemera. He also had a big bust of Lenin that nobody in Lithuania wanted.

The day Lithuania declared independence in 1990 was the day they began to expunge the Russian legacy. They condemned the occupation as an illegal act. The display of Russian symbols and imagery was officially banned. They started removing Moscow’s monuments, including all the busts and statues of Lenin.

Nobody knew how many there were, but since the Russians had been the controlling colonial power in Lithuania for almost five decades, everybody knew there were plenty. The busts and statues were a big part of the Communist Cult of Personality and their propaganda machine. Everybody knew where at least one of them was. They got pulled down, smashed to bits and pieces, and thrown into the dust bin of bad history.

The Lithuanian general had hedged his bets and it was paying off. He sold everything he had to Russell Bundy, who had taken a great interest in the memorabilia. “He saw the bust and it was love at first sight,” Rita said. “He never said why, at least not to me. I don’t think dad knew, either. He took the collectables back to Urbana, got lots of mannequins, set up a room for them, dressed them in the Russian uniforms, and displayed them in the room. It wasn’t public. It was private. You had to be invited to see it. I saw it once. In the meantime, he waited for dad to bring the head of Lenin to him.”

Our father got the necessary export papers rubber stamped and got the bust crated. It was taken by truck to Hamburg, Germany. From there it was loaded onto a freighter. When the freighter docked in Philadelphia it was unloaded and taken by truck to Urbana. Once there it was uncrated and set up for display.

I met Russell Bundy once, by accident, at my parent’s house. I had driven there to drop something off. He was talking to my parents about his daughter Beth, who was married to a man named Joe. They lived in Pennsylvania, where Russell Bundy was originally from. They wanted to adopt a child. Beth wasn’t able to have one herself. She wanted a newborn baby. It was proving difficult to find a newborn in the United States. It was much easier finding one in Eastern Europe. They were thinking of trying to find one in Lithuania.

When I saw him my first thought was he looked like Robert Preston in the movie “The Music Man.” He had a similar manner, too, lively and engaging. “He has a huge personality,” my sister had already told me. He had a terrific, sincere-looking smile. He was wearing a sleeveless argyle knit sweater and a bow tie. He was also wearing a wig, the kind of wig, like the kind Andy Warhol used to wear, that was obviously a hairpiece.

“His daughter Beth told me she never saw her father without his wig,” Rita said. “She said none of her brothers and sisters ever saw him without it, either.”

“What about his wife?’

Russell Bundy and his wife Elizabeth were married for fifty two years. “No, I never wanted to ask her about that and I never did.”

Some people wear wigs to dress up their hair, which is in bad shape. Others wear wigs because they have gone bald. I didn’t know what it was with Russell Bundy, but since he was a salesman kind of man, I thought he probably lost his hair at an early age. The wig helped keep him looking young and vibrant. I couldn’t help wondering, since he was a big time businessman, if he ever flipped his wig like other big time businessmen are prone to do.

The bald headed pate of Lenin wasn’t the only large object on display at Bundy headquarters in Urbana. There was the World’s Largest Loaf of Bread Sculpture, too. It is made of steel and fiberglass. “It’s exactly as it’s touted,” said Daniel Kan from Dayton. “It’s a large loaf of bread that is lit up from the street. You can pull in and take pictures. It’s definitely a two picture moment.”

There are actually two monumental loaves of bread. “Formerly displayed upright, the larger of the two is now lying behind one of the factory buildings,” according to World’s Largest Things. “It attracted a lot of attention, painted with the package design of one of their customers, which you can still see on the leftover loaf. The second loaf acts as a sign for the factory itself, displayed by the entrance door. The larger of the two is a little more interesting, as the plastic bag is more irregular, and the twist-tie looks as if it’s been used a couple of times.”

Russell Bundy had meant to deliver capitalism to a recently Communist country, but instead had brought a bit of Communism to a capitalist country. He was a dyed-in-the-wool entrepreneur but had paid good money for and transported a collectivist icon more than five thousand miles to Ohio, one of the more conservative states in the country. Urbana is in the 4th Congressional District. It is a Republican town. The combative MAGA man Jim Jordan represents the district in 2025. The locals call their home Mayberry as in TV’s once popular “The Andy Griffith Show.”

Most Westerners have a negative view of Lenin, seeing him as the initiator of Soviet totalitarianism, political repression, and a failed economic system. He created the Cheka secret police force, which is considered a foundational instrument of state terror. There wasn’t much to like about Vladimir Lenin.

Everybody liked the bust, however. There was something heroic about it, just like there was something heroic about Lenin. His early aims were rooted in the ideals of equality, freedom, and brotherhood. After his older brother was executed for his part in the attempted assassination of Tsar Alexander III in 1887, Lenin made a commitment to revolutionary change. He kept at it for thirty years. Then, to his surprise, just like that the Russian Revolution happened, ending centuries of imperial rule. He embraced terror and violence to get what he wanted. He came to believe the ends justified the means. In the end what he achieved was a one-party autocratic state. By the time he became the top dog of the Bolsheviks, who became the Communists, he didn’t believe in equality, freedom, and brotherhood anymore. He believed in every man for himself and the state against all.

The bust might have been a remarkable thing, but I never saw it. I wasn’t especially interested in looking at a boulder depicting a dead Big Brother. I asked my sister what she thought of it, since she had seen it.

“I thought it was ridiculous,” she said. “But Russell loved it. He stood beside it smiling like the cat who swallowed the canary.”

Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.”

“Bomb City” by Ed Staskus

“A police procedural when the Rust Belt was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. Revenge is always personal. It gets personal.

A Crying of Lot 49 Publication