By Ed Staskus

It was the morning of the autumnal equinox, day and night balanced. It was the end of summer. The Azores anticyclone would be coming back soon leading to an Indian summer, but for now the outdoors was wet and brisk. It was once thought otherworldly things happened on the equinox, things like Gediminas, the Grand Duke of Lithuania, dreaming about an iron wolf foretelling the building of Vilnius. Since then residents of the capital celebrated the equinox and Duke Gediminas Day, the birthday of Vilnius, on the last weekend of the month. On Sunday night, at the end of the festivities, a straw billy goat, a symbol of fruitfulness, was ceremonially burnt.

It was the first anniversary of his wife’s death and Ignas Petrauskas had gotten up early, ordered flowers, eaten breakfast, and drank a cup of strong coffee while skimming through the national newspaper, Echo of Lithuania. When he was done with his second cup he would go to the Rasos Cemetery and lay the flowers at his wife’s grave. The coffee was good. The newspaper was filled with bad news. He put it aside. He looked out the window at the Vilnia River.

He lived in Uzupis on the east side of the river across from the Old Town of Vilnius. It was a small apartment on the riverbank, but modern, unlike most of the neighborhood, which was the worse for wear, although it was slowly being gentrified. In the meantime it was filled with bohemians and artists from the nearby Vilnius Academy of the Arts. A statue of the American musician Frank Zappa was around the corner, erected by local artists proclaiming the spirit of the place. They called their place the Republic of Uzupis.

There was a plaque on nearby Paupio St. that read, “Everyone has the right to hot water, heating in winter, and a tiled roof. A cat is not obliged to love its owner, but must help in time of need. Everyone has the right to be unique.”

Most of the inhabitants of Uzupis, which meant “beyond the river”, lived there because the rent was dirt cheap. Some squatted free of charge anywhere a landlord was non-existent. Ignas wasn’t a bohemian or an artist. He was a police detective assigned to the General Prosecutor’s Office.

He wasn’t bothered by the idiosyncrasies or rough and tumble of Uzupis He had served as a military policeman with the Komendantskaya Sluzhba in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s during the Red Army occupation of the Central Asian country. A yellow letter “K” on a red patch worn on his right sleeve made sure everybody knew what his job was. He had not been able to settle the question during his two-year tour of duty of who was worse, the Mujahadeen or the Soviet Armed Forces. He finally resolved the question by cursing the both of them.

“Velniai griebtu,” is what he said. He meant “May devils grab you.”

He got married soon after returning to Lithuania, to Birute, a girl from his hometown of Smiltyne on the northern tip of the Curonian Spit. When the Russians were dislodged after more than four decades of occupation, and a new Law on Police was enacted in December 1990, providing a legal basis for a Lithuanian police force, they moved to Vilnius. It was at the other end of the country from Smiltyne. He joined the force, making his way up the ladder to the Criminal Police. He briefly worked with the Organized Crime Bureau before being assigned to the General Prosecutor’s Office..

Ignas bought his new apartment after Birute’s death. He sold their house. It had become lonely, full of nothing but memories. No matter how good the memory it was like the shard of a broken mirror. His marriage to Birute had been good. They understood each other. He liked the way she smelled. They liked getting into bed together at night and getting up together in the morning. They went for walks on summer weekends to Story Park where there were many wooden sculptures based on folklore and Hill Park where they picnicked at the Hill of Three Crosses. They made each other laugh. Now she was gone forever.

He visited her grave once a month. Rasos Cemetery was the oldest graveyard inside the city limits of Vilnius, going back to 1801, when the first person, Jonas Muller, the Burgomaster of the city, was buried there. New burials were restricted to family graves, but since one of Birute’s grandfathers was buried there near Jonas Basanavicius, editor of the first Lithuanian-language newspaper and one of the signers of the Act of Independence in 1918, Ignas had been allowed to bury his wife there.

Somebody had swerved onto the sidewalk outside their house late one night when Birute was walking home and struck her. It was a hit and run. She might have lived if she had been found sooner and treated. She died of internal bleeding. The driver was found and arrested a week later. He lived nearby. The day he was being taken to the Vilnius Regional Court for an initial procedural action Ignas waited at the side entrance door. When the man stepped from the back of the police transport truck, blinking in the sunlight, Ignas bull rushed him, punched him in the face, knocked him down, and continued punching him until he was pulled off. He might have killed him otherwise. He broke the man’s nose, his jaw, cracked an eye socket, and knocked out three teeth. He broke his own hand. He was suspended and put on medical leave for a month. Afterwards, when he was back at work, nobody ever said anything about the incident, which he was thankful for.

Ignas always walked to the cemetery. It was less than a half hour from his apartment. He put on a pair of boots and a leather coat. It was a utility coat with snap closures and front flap pockets. He positioned a hat with a downwards-sloping brim on his head. As soon as he stepped out the door, however, it started raining harder. It was much windier than he thought it would be. Heavy rain drops drummed on the crown of his hat. He walked across the bridge to the Old Town and caught the No. 89 bus to the cemetery.

Rasos Cemetery was located on two hills with a valley separating the hills. Birute was buried on one of the hills. He took a footpath he knew by heart. By the time he got to Birute’s grave the wind had died down. He pulled his flowers out of the plastic grocery bag he had brought them in. They were rues with bright yellow cup-shaped blooms, tied together with a black ribbon. The flowers were believed to ward off evil. He lay them down.

Ignas stood in front of the headstone quietly for ten minutes. He didn’t notice that it had stopped raining. When he was ready to leave he stepped up to the headstone and laid his hand on top of it. He had often rested a hand on Birute’s thigh when they were together on the sofa in their living room, she sewing and he reading. The memory made him feel empty.

He took the same footpath leaving Rasos Cemetery, but since the bad weather had taken a break he walked back to Uzupis instead of taking the bus. He put his hat, boots, and leather coat away. He mixed a drink of vodka. honey, and cinnamon in a water glass to warm himself up. He sat down. Heavy clouds shortened the afternoon. He watched the rain coming back through the glass door leading to the balcony. He made another drink. It got dark the minute sunset happened and he got sleepy. He fell asleep.

Ignas woke up to the sound of the telephone ringing. He was surprised it hadn’t stopped ringing by the time he got to it. It was past nine o’clock. He lifted the receiver, wiping away a soggy spot from the corner of his mouth.

“Labas,” he said.

“Labas,” the voice of his boss in the General Prosecutor’s Office said.

“How is everything?”

“As good as can be expected.”

“Is something going on?”

“Yes, I need you to go to Siauliai.”

“What’s happened?”

“An American has been found dead.”

“That’s not good.”

“No, it is not. An agreement on investment with the United States has just been arrived at and now this. Their embassy has been informed about the death, but we are leading the investigation.”

“What about the Criminal Police?”

“They are deferring to us on this one. They suggested you.”

“Why me?”

“You have experience with criminal gangs and the Russians.”

“Are they involved?”

“Siauliai seems to think they might be, one of their dirty tricks. I don’t put it past them, but they’ve got their own problems right now, what with Chechnya and the ruble going downhill.”

“Was it murder?”

“I don’t know for sure, but, yes, it seems so. The local police aren’t saying much, although they did say it was the third such death in the past month. The other two were residents.”

“Are they saying the deaths were similar?”

“Yes.”

“How soon do you need me there?”

“As soon as possible, Go as soon as there’s light.”

Siauliai was two hundred-some kilometers from Vilnius, which meant between two and three hours of driving, as long as the road hadn’t caved in somewhere along the way. Sunrise was at about seven o’clock. If he was on the way by then he would be in Siauliai no later than ten in the morning.

“Am I going alone?”

“For now, yes. If you need help, call me, I’ll send a second man.”

“All right.”

After Ignas’s boss hung up he went to the bathroom, washed his hands and face, brushed his teeth, and slipped into a pair of pajamas. He got into bed. He lay there unable to fall asleep. He had spent many sleepless nights since Birute’s death. He missed the smell of her and the sound of her breathing. He missed the feel of her pressed up against him. He missed her heartbeat. He felt lonely in the dark. He got up and sat on the side of the bed.

He took thirty steady breaths and then another thirty. It was something he had learned to do. He wasn’t going to be any good in the morning if he didn’t get some sleep. There was a framed photograph of Birute on the dresser. He got it and put it face up on the other pillow. He got back under the covers and soon fell asleep.

The rain stopped sometime before dawn. On the heels of the rain the rest of the cold front blew in from the Baltic Sea. The wind got gusty. It snapped tree branches. When the alarm clock went off Ignas turned it off. He got up, shaved, brushed his teeth again, and put together his two travel bags, one of them toiletries and clothes and the other one his investigation kit. The tools in the kit included measuring tape, a flashlight, magnifying glass, notebooks and pens, a recorder, binoculars, a fingerprint kit with lift tape, tweezers, forceps, glass vials, a scalpel, chalk, evidence bags, and a 35mm camera loaded with color print film.

He checked his Browning Mark III. It was a 9mm pistol with a thirteen round magazine. He packed an extra magazine. When he was working he carried the black pistol in a hip holster. He attached the holster to his belt. He turned off all the lights and locked the door of his apartment. When he got into his Audi five-door wagon he saw he needed fuel. There was a Statoil station two or three minutes away. He drove to it and filled up with diesel.

He pulled over to the side and unfolded a road map. The A2 would take him to Panevezys. From there he would take the A9 to Siauliai. He would stop along the way for coffee. He had neglected to bring a hat. He would have to buy a new one. In Scotland they say “It’s Baltic out there” whenever there is bad weather. He didn’t think the weather was going to get any better in the Baltics anytime soon.

Excerpted from the book A Murder of Crows.

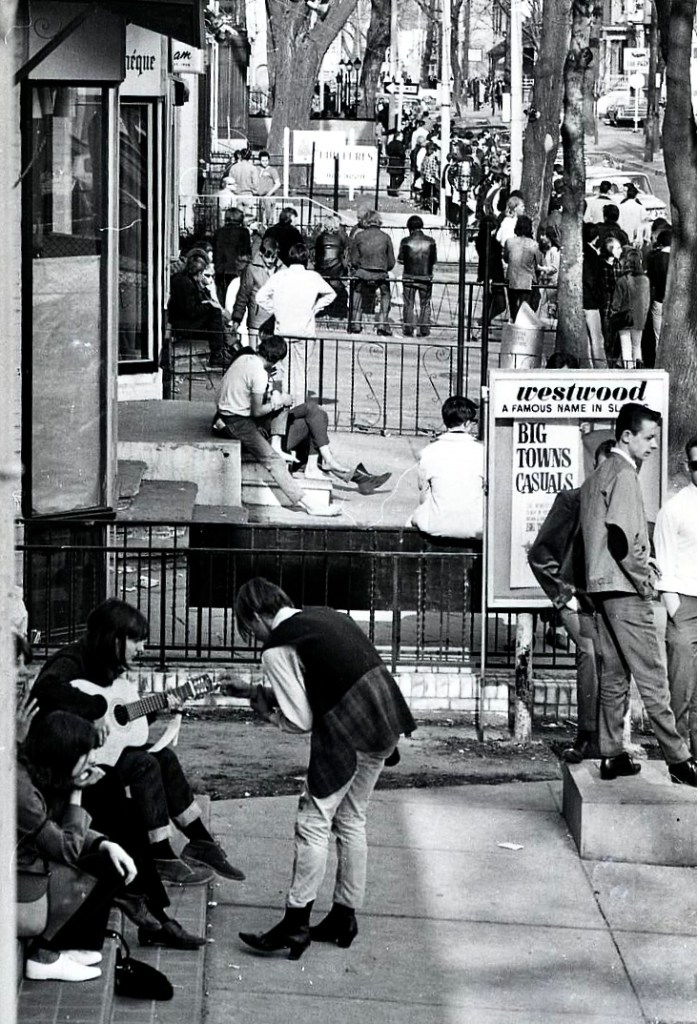

“Made in Cleveland” by Ed Staskus

Coming of age in the rough and tumble of the 1960s and 1970s.

“A collection of plugged in street level short stories blended with the historical times, set in Cleveland, Ohio.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Books

Available on Amazon:

A Crying of Lot 49 Production